This is a repost of my newsletter, The Civic Pulse, which I am crossposting to the blog. If you like the newsletter, subscribe here: https://civilytics.substack.com/welcome

Friends and Colleagues,

I usually do not send these newsletters so frequently, but every day feels like a week these days. I’ve been doing municipal budget analysis and strategy work with grassroots organizations in a number of cities (Phoenix, Philadelphia, Providence, Baltimore, New Orleans, Dallas and more) and I wanted to share out some of what I’ve learned from this work.

I have heard from many friends and family who started following and supporting some of the community organizations I referenced in my last newsletter – thank you! I want to thank you for the conversations that has sparked. I also want to speak to the discomfort some of us might feel when hearing terms like “divest from policing” or “abolish the police.”

To understand the police abolition movement, it helps to begin by thinking of the demands around policing in America as a continuum with 4 positions. I want to talk about each of these, give you some resources to learn more about them, and share with you how I’m thinking. I hope you find this helpful in finding your own place along the continuum.

- Reform: Make police less bad.

- Accountability: Watch the police closely and constrain their behavior.

- Divest/Invest (#defund): Reduce the role of police in a society and replace some policing with community approved alternatives.

- Abolition: Eliminate policing and replace it with social services and enforcement by other means.

Reform

Reform has been the dominant position taken by policing scholars, critics, and politicians in the last 20 years and policing as a field has responded to public criticism by proposing ways to be better. Advocates of reform tend to focus on research-based approaches showing how rules, norms, and policies can constrain police and reduce incidents of violence against civilians.

The current best example of this position is the #8cantwait campaign, which proposes a set of policies that promise to reduce officer-initiated violence and purport to be backed up by research. However, as Philip V. McHarris and Cherrell Brown, sociologists and scholars I deeply respect write, the proposal is backed up by bad science and promotes policies that have already been adopted in places where police continue to commit acts of violence, including Minneapolis. One of the policies, by the way, is to require officers to notify civilians before firing on them – what good would that do for someone like Tamir Rice?

Reform is important but I implore you to be bolder and think bigger in this moment. We do not need iterative “data-driven” solutions. One of my favorite writers about our current moment has a way of cutting right to it:

There’s a special kind of privilege in always asking for new information and “evidence” before making a policy recommendation – a lack of urgency when it is not your life, family, property at stake. It’s also a rejection of other ways of knowing – of lived experiences and trauma.

But, even were that not the case, we also have a decade of evidence that “proven reforms” have not made our system safer. This evidence is summarized in two excellent Twitter threads I recommend you read below:

One from John Roman:

One from Mike Shor:

This leads others to take a different position on the continuum, demanding not just reform, but for us to change the contract between communities and police departments through new accountability rules.

Accountability

Cops do not investigate cops. District attorneys do not charge cops. And judges do not sentence cops. This lack of police accountability is on full display right now. Police brutality while police are in the spotlight is continued evidence that police believe they can disregard their written policies and act with impunity – across the country. This belief is the result of years of little to no oversight. This is why accountability is needed.

And we know how to do that. We can take the responsibility for holding police accountable away from district attorneys (DAs) and police departments and put it in the hands of a dedicated state agency with power to subpoena records, license police officers, investigate them, and set department standards. Empowering that state agency to revoke the license of any officer who violates the code of conduct is critical: officers without a license would no longer be eligible to serve as police officers in the neighboring town – just as is the case with teachers, lawyers, doctors, and barbers.

This is where I began my journey and I have thought a lot about why K-12 education accountability is a good model to build upon. A group of law enforcement professionals have proposed another interesting accountability framework; give it a read.

You don’t hear about accountability because it isn’t the demand of the moment. The Movement for Black Lives and many Black, Latinx, and indigenous community organizations have a broader goal: defunding police departments to shrink their size and limit their scope. These organizations have been in this struggle for decades.

Defund or Divest

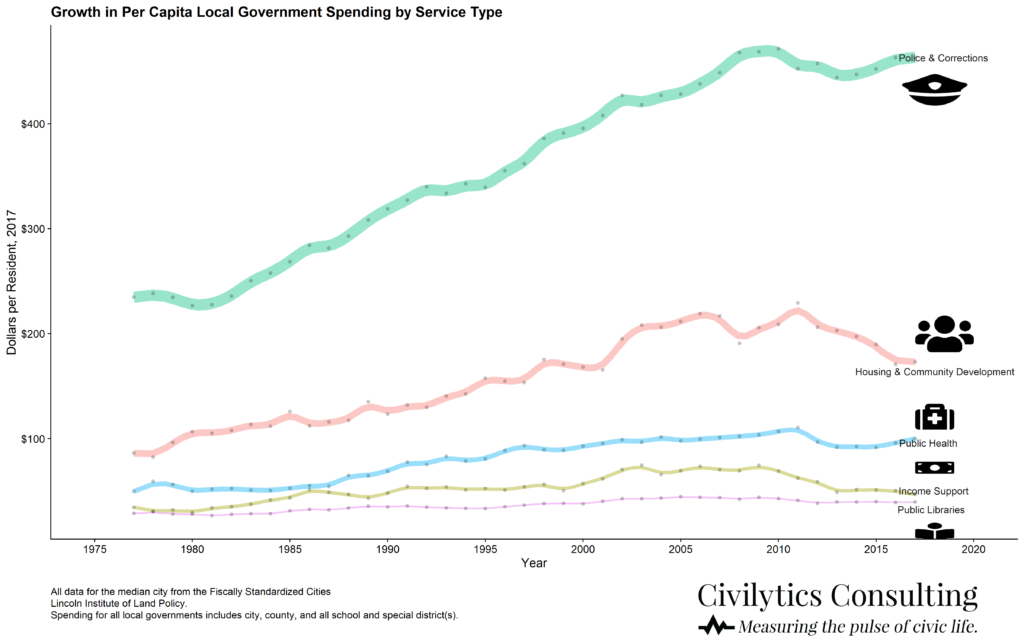

Police budgets are historically untouchable, even in the steepest sharpest of economic downturns. The strongest accountability mechanism that city governments have to change behavior is budgetary – but that mechanism is all but gone for policing. Here is the municipal spending on several public services across the largest 150 cities in the U.S. Look at how we have doubled per resident police spending while barely increased our spending on other critical services like public health, housing, income support, and public libraries (all $ expressed in 2017 dollars so these are real changes in purchasing power):

The Upshot did another analysis of the same data.

Divestment does not mean simply imposing austerity measures on police, though. Divestment means opening up reinvestment in communities to meet residents’ unmet needs. On Friday evening I was working with community organizers in Philadelphia to get a reinvestment proposal in front of the city council. The proposal fully funded many housing, violence prevention, and economic development programs that had substantial political support, but for which money was never able to be found. The proposal showed that all of these programs could be funded by a 7% reduction in the number of police officers.

Divestment is not just an argument we need to hear because it’s our democratic responsibility to listen to Black voices, it is also a fiscal and economic argument we need to confront as we face one of the biggest budgetary crises ever. Budgets will be tight this year and next. Our memories of George Floyd, Ferguson, Tamir Rice, and all the others need to be long.

Divestment is not about punishing police – it’s about boldly reshaping our society.

Abolish the Police

When I first met with the Racial Justice Action Center in Atlanta as I was beginning this work, they told me about a grassroots study they conducted to understand the needs of their communities. When they asked about residents’ biggest safety concern, residents’ overwhelming response was: the police. The police presence was the danger. Not gangs. Not guns. Not drugs. If you are Black, the police are dangerous. If you are Black and trans, the police are even more dangerous. Read their report – it will break your heart.

So when another organizer told me their goal was the “abolition of policing” I was able to set aside my first reaction – what will replace them? how will you pass it? – and listen. And I kept hearing this as the goal. And I kept listening and thinking about it.

And then it clicked.

I realized abolishing the police wasn’t that radical at all.

You see, I live a police-free existence. Many of you do as well.

The only time I encounter a police officer is at a large event or when I am driving. Police do not walk down my street. They do not regularly drive down my street. If an officer carried a rifle down my street I would call the city and demand (and get) an explanation. And police do not stop me – in the Boston metro area I am not sure what I would have to do driving to warrant a traffic stop but I can assure my car is not capable of achieving it.

For me, police are functionally abolished, yet my life is not full of crime and violence. I’m safe.

The demand of police abolitionists is in fact quite simple – they want what I, and most of you, have. A police-free existence. Yet, these voices are not being heard in the rush to reform policing.

Black lives matter means Black voices on police presence in our communities matter. White voices have led to decades of uninterrupted investment, militarization, and paper-only reforms that have not abated the violence.

When George Floyd was murdered and you said you would listen – is abolition what you heard? If it isn’t, please, give it a listen and consider it. You may see it’s not as radical as you first thought. But don’t take my word on it, read Mariame Kaba’s powerful words on what abolition means.

Thank you. Please give money to your local racial justice advocacy groups