Plus catch my presentation at STATS-DC later this month!

There’s been lots of discussion of “crime waves” in the past few months. One thing I cannot emphasize enough is how detached these conversations are from both the empirical evidence and the lived experience of violence in the U.S. Whether you are interested in data and measurement, or concerned about how we make safer communities, we’ll talk about the issue from both angles in this edition of The Civic Pulse.

In this newsletter you’ll learn:

- How to unpack the discourse around crime and resources to help understand the debate and people’s real needs

- How to catch my upcoming presentation at STATS-DC on the dashboard prototyping process

- How ARPA aid continues to roll out to local governments and what you need to know

- A link roundup

Also a quick note of thanks to all of you who read, shared, and replied to our last newsletter. As we said then, getting media coverage of our work is a pretty big challenge, so we really appreciate all the kind words and help raising awareness of our work!

On to the topics.

Crime “waves” and defunding the police

The past couple months have brought lots of hot takes on how rising crime rates are related to defunding police — and other similar arguments. These hot takes are based on preliminary data from a basket of cities that saw increases in gun violence and homicide in 2020. The dominant narrative that’s emerged from these glib reads of the data, and that’s been reinforced and repeated by the Biden administration, is that more and better trained police are needed to meet this challenge. In a new guide, co-authored with and informed by community organizers around the country, we look at this claim in great depth.

The guide covers some major issues with this narrative including that:

First, the evidence for a “wave of violent crime” is based on incomplete data and is overgeneralized. Much of the coverage is based on data from fewer than 100 cities, and doesn’t include prominent cities in this discussion like NYC and Chicago. And, the data and discussions ignore the reality that violence is usually a neighborhood by neighborhood phenomena. Whether the national crime rate is rising or falling is of little comfort or concern depending on whether you live in an area experiencing an outbreak of violence or not. *

Second, the social science evidence does not support the conclusion that police prevent violence for a few reasons:

- The most rigorous available studies of the effect of police on rates of violent crime, and particularly on homicide rates, are inconclusive

- The very real negative impacts of policing — surveillance, property seizure, and killings that too often go unpunished — are not included in crime statistics or in policy evaluations of policing

- If you are interested in social science research, I encourage you to look at the guide’s appendix for a recap of the flaws in the studies cited by “experts.”

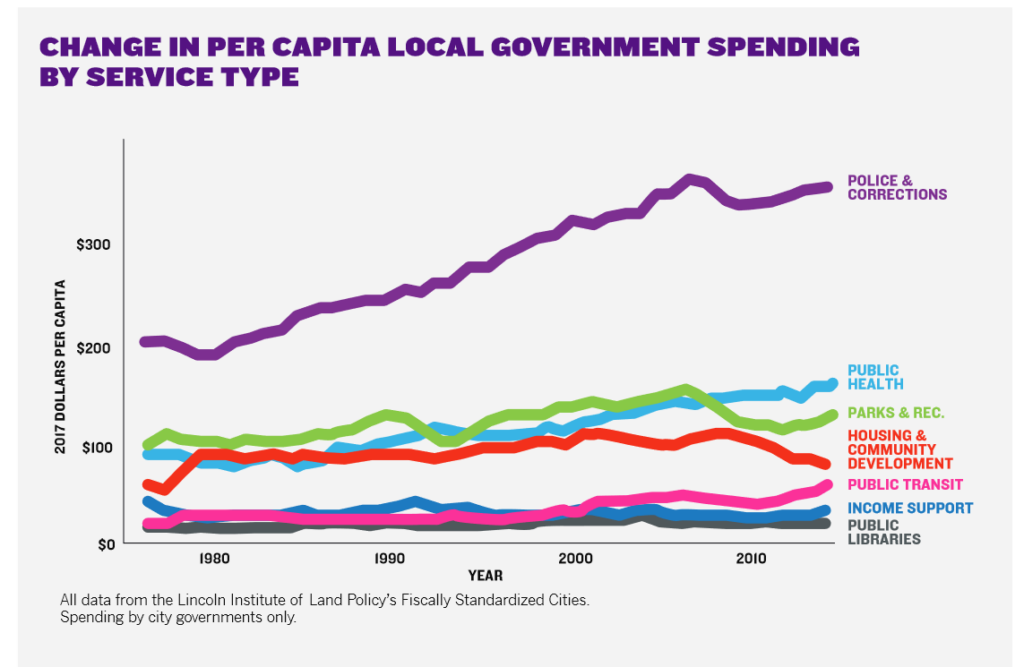

Third, as this chart from the guide shows, we’ve been doing the policy experiment on investing more and more money in policing (after adjusting for inflation) while failing to invest in or actively defunding other important public services. There are a lot of policy options we haven’t tried to stop violence, like investing more in other public services.

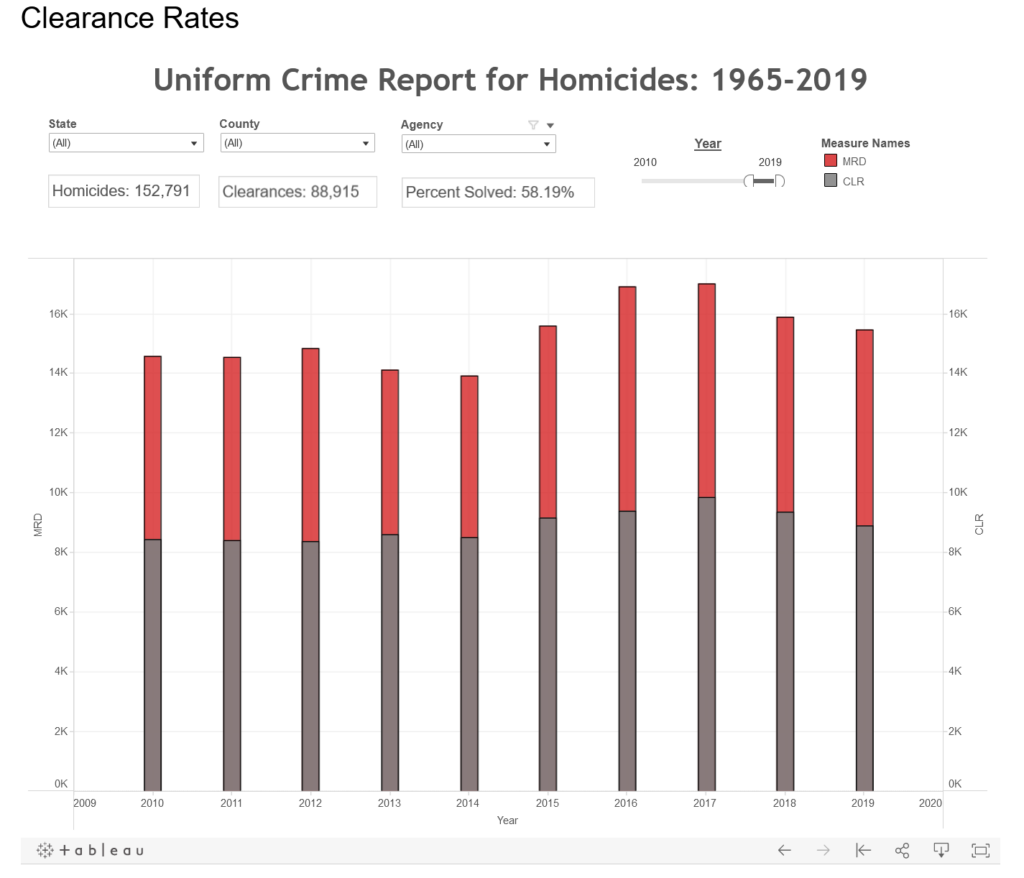

And, even with all the funds spent on policing , I encourage you to look at how few homicides in the U.S. are solved annually — arguably, police’s most important job. Over the last decade, 40% of homicides have gone unsolved (that’s 60,000 people’s deaths). The Washington Post did a heartbreakingly detailed investigation into how murder goes unsolved in low-income communities of color in cities across the country.

Finally, it’s important to keep in mind that the institution of policing is about enforcing the law, not about preventing crime (officially, police are known as law enforcement officers, not crime prevention officers). In our work on local budgets this year, we’ve typically seen cities spend less than 1/100th of what they spend on policing on violence prevention programs (if they have such programs at all), despite the fact that violence prevention programs have fewer negative externalities, create community trust, and have been shown to be effective.

We know what stops violence: stable housing, meaningful employment opportunities, access to healthcare and education, stronger community bonds, and mediators to address disputes. Community leaders have been showing up at city council and county commissioner meetings demanding these solutions — it’s time to listen.

Presenting at STATS-DC on Educator Diversity and Dashboards

Are you interested in Using Data to Improve Educator Diversity and Understand Students’ Access to Teachers of Color? Or in creating public education dashboards? If so, you may want to check out my upcoming presentation with Meg Caven from REL Northeast & Islands and Christopher Todd from the Connecticut Department of Education Talent Office.

On Friday, Aug. 20, at 11 Eastern, we’ll be discussing how we are designing and implementing a tool to help schools and districts understand and measure the access their students have to teachers of color.

One part of the project I’ve enjoyed is developing a prototype using available public data (with some unit-record data simulation for good measure!) so we can work through the design with content experts without worrying about pupil privacy. This approach has allowed us to focus first on the most important pieces of information to share with users consider how to make the dashboard compelling and easy to use from the start.

The 2021 STATS-DC Data Conference is completely virtual and free to attend. You can register for the event at the conference website.

For me, this is a bit of a return home since I have fond memories of many STATS-DC presentations about open data and applied research within education agencies from my time at the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. I hope to see some familiar faces and catch some great sessions at this year’s event!

More on the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA)

We enjoyed reading some of public comments submitted to Treasury about the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds during the open comment period. (You can read our public comments here.) We’ll be updating our guidance and FAQs when the final regulations are published in the next month or two.

In the meantime, we published 7 more ideas for how communities could use ARPA funds along with some back-of-the-envelope pricing for each idea. Our goal in publishing these is to encourage communities and organizers to think bigger and bolder about how to use ARPA funds, not to say these are the “best” ideas for a given community.

I also presented at a teach-in presented by the People’s Coalition for Safety and Freedom on how federal funding works. You can view their teach-ins on YouTube. I spoke about what makes ARPA aid unique: that it’s largely unrestricted, is a tremendous amount of money, and has few restrictions on the process of allocating the money or requirements for reporting on its use after the fact.

The most important message to get across is that the funds are not yet spent. Local officials may have strong ideas of what they want or need to spend the money on, but until the checks have cleared, you still have time to make your voice heard.

If you are looking for a place to get started, Cortney Sanders of the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities shared two great papers at the Teach-In that I highly recommend:

- Three Principles for an Antiracist Equitable State Response to COVID-19

- Priorities for Spending ARPA Fiscal Recovery Funds

What we’re reading and thinking about:

Five Strategies for Using One-Time Funds on School Staffing – WestEd

If you work in education and are looking for ideas on how to leverage one-time funding from ARPA or other sources to address structural underfunding and personnel shortages, this brief guide has five great strategies. One I was glad to see was engaging with community organizations to think creatively about investing in capacity long-term.

Results from a National Survey on Public Education’s Response to COVID-19

AIR put together an excellent set of reports and infographics detailing the results of a national survey on how public schools adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic. This kind of comparison is critical to understand different choices communities made and why, and to help think about what school will and should look like moving forward.

A View of the Louisville Police from the Ground

“If racism is a public health crisis, then the Louisville Metro Police Department is a tumor. And a tumor can’t cure itself.” ~ Shauntrice Martin. This entire essay is worth your time to get a glimpse at the lived experience in many communities across the country. I’m lucky enough to have learned a lot from Shauntrice, who among many other talents, runs a Black owned grocery store serving Louisville’s biggest food desert!

Academic Corruption and the Facade of Objectivity

Juul, the vape company, bought an entire issue of the American Journal of Health Behavior (AJHB). The company paid $51,000 to place 11 studies they funded linking vaping to smoking cessation. FDA regulators often look at studies published in venues like AJHB to inform their decisions, and the FDA is currently reviewing Juul’s products. While the Juul case is a more flagrant example of the facade of objectivity, the article describes how the practice is more common, and less blatant, than you would think. But, hey, at least Juul paid extra to put the research outside of a paywall.

A Deep Dive Into the Nitty-Gritty of Our Crime Stats Infrastructure

First, if you don’t follow Rajiv Sethi’s recent work on police and violence, you should, immediately. Second, you know I love a good deep dive through administrative data and all of the twists and turns that arise due to reporting requirements, data entry procedures, input errors, and other glitches. This carefully written roadmap through available data on policing in the U.S. is eye opening and a critical read for anyone wanting to work in this space.

Fewer Low-Level Arrests = Lower Crime and Fewer Police Shootings

An interesting analysis at FiveThirtyEight that looks at how different choices in cities about how many low-level offense arrests to make affects crime rates and shootings by police officers. We need much more descriptive work like this.

Finally our local online newspaper did a write-up on Civilytics and our recent work on the disparity in ARPA aid affecting our town among many of others.

As always, we appreciate your help spreading the word about this newsletter. If you haven’t already, please subscribe. If you subscribe, send it to a friend, or share it on social media. We appreciate every bit of help spreading the word.

And, we love to hear from you! If you’ve got a project you think Civilytics can help with or a question, do get in touch.

With gratitude,

Jared

- *For a fuller critique of this cyclical discourse on crime and police spending, see this excellent essay by Alec Karakatsanis: https://www.currentaffairs.org/2020/08/why-crime-isnt-the-question-and-police-arent-the-answer