Learn About Policing in Your Community

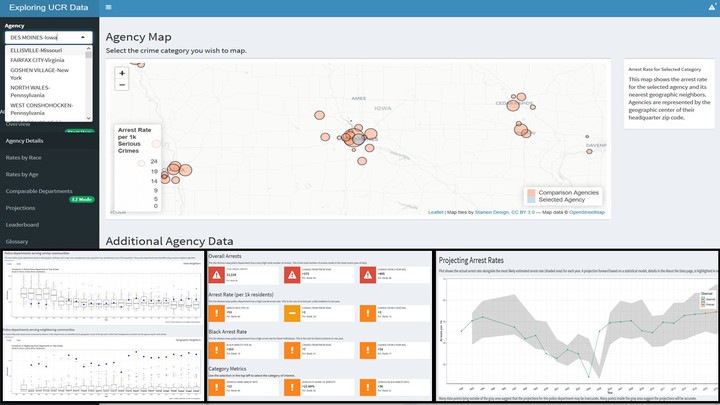

Visit the Arrest Data Explorer prototype today and learn about the patterns of arrests by police departments in your community.

With this tool:

- You can explore data visualizations about over 4,000 police departments nationally

- You can analyze trends in police action over time to contextualize reported arrest numbers

- You can compare each police department to national, regional, and demographic reference groups

- You can review projections of future police activity

Try the prototype out today! And, if you have feedback on what you would like to see in such a tool, please get in touch.

Follow us on social media to stay updated on this project.

The Motivation

Despite the recent uptick in national political activism, local civic participation and trust in government is in decline in the US today (Putnam 2000; Skocpol 2003; Ryzin 2011). One contributing factor is that the government is more responsive to technical experts than to members of the public. The public recognizes this and feels little chance of being heard on important policy issues (Fischer 2009). While technical expertise is needed to remedy the challenges that we ask government to solve (e.g., clean water, safe streets, quality schools), the diminished voice of the public poses a threat because technical experts do not represent everyone’s values and priorities. As Virginia Eubanks writes, there is a difference between arguing on behalf of the poor and arguing from the position of being poor (2018). This is one of the fundamental tensions of democracy today: how can government be accountable to the public it serves while harnessing expertise to achieve its goals (Behn 2001)?

The answer is a participatory form of democratic accountability that places technical expertise in the service of stakeholders. The need for such an approach is urgent in policing. Police departments rely on complex data analytics and surveillance systems to conduct their work. The public has little access to these data or analytics and, as a result, is left to advocate with anecdotes and value statements to which policymakers are less receptive. Existing tools to help the public understand police activity represent the goals of their creators — such as profit, cost control and efficiency, or a one-time special report. In most cases, the data and methods are kept secret, verified by no outside entity. Evidence-based public deliberation around these issues is thus reduced to selecting among policy positions crafted by well-resourced organizations with no accountability, review, or auditing of the data or methods used. By denying the public an active role in asking questions and gathering evidence, an impoverished and unappealing form of civic participation emerges — discouraging the public from lending a voice at all.

A more democratic approach would be a co-created public infrastructure that supports participant-led inquiry into government performance. For any policy area, the first component of this approach is an open-source, auditable collection of data and analytics accessible to all stakeholders including community members, government agencies, journalists, and researchers. On top of these data, audience-specific tools should be constructed to allow users to pose their own questions and construct their own analytics. We know that the public, when motivated and perceiving a chance to be heard, can mobilize technically sophisticated tools of argumentation (Epstein 1996).

My Contribution

Such tools do not exist yet because their creation requires a new design process that places a diverse group of stakeholders, and not the data scientist, at the center. As a first step in this conversation with stakeholders, I have built a prototype to interactively explore police arrest data across the United States. I invite you to explore it today: https://jknowles.shinyapps.io/arrest_prototype/

Its purpose is to begin a design conversation with stakeholders by demonstrating what is possible and inviting them to imagine what could be. The prototype does not target any particular audience, but instead surveys the many possiblities for exploring police data and measuring police activity that stakeholders may find useful.

Roadmap

Building a prototype is only the first step. The next steps include:

- Identify stakeholders from each of four audiences: organizations advocating police police departments, reform, journalists, and academics.

- Iteratively refine the tool together with these stakeholders

- Develop audience-specific user guides for the tool

- Publish the tool, data, and source code online for anyone to use

- Engage and train stakeholders from each audience to contribute to the tool

The result will be a model for modern civic discourse; empirically grounded, representative of the public’s values, and available to anyone to review, revise, or rebut. This approach can then be applied to other public services like fire protection, healthcare, and environmental conservation. For Civilytics, policing is the first step.

Learn More

I am looking for partners to join Civilytics in this exciting and important work. Contact me with inquiries about the prototype, the roadmap, partnership opportunities or to discuss the intersection of expertise and democracy. If this is you, please get in touch.

Further Reading

Behn, Robert D. 2001. Rethinking Democratic Accountability. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Epstein, Steven. 1996. Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Eubanks, Virginia. 2018. Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Fischer, Frank. 2009. Democracy & Expertise: Reinventing Policy Inquiry. New York: Oxford University Press.

Putnam, Robert. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon; Schuster.

Ryzin, G. G. Van. 2011. “Outcomes, Process, and Trust of Civil Servants.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21 (3): 745–60.

Skocpol, Theda. 2003. Diminished Democracy: From Membership to Management in American Civic Life. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.